Menopause Can Shrink Uterine Fibroids

One of the most common gynecological tumors is leiomyoma (fibroids). It affects 30 to 50% of women of reproductive age.

One of the most prevalent diseases of the female genital tract is uterine leiomyoma, also known as fibroids or fibromyomas.

Leiomyomas are benign tumors that originate from the smooth muscle cells of the myometrium, which is the thick middle layer of the uterine wall. It contracts during childbirth and menstruation. As a result, leiomyomas can increase the risk of infertility, spontaneous abortion, or other problems during pregnancy.

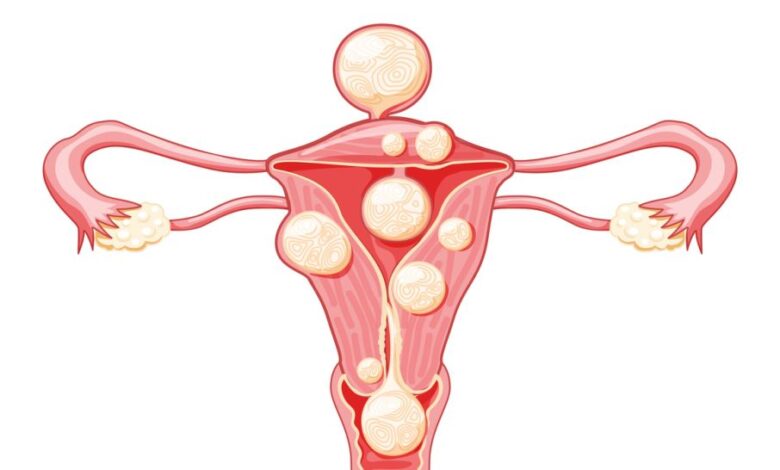

Uterine leiomyomas can be classified based on their location in the uterus and can range from small, barely visible ones to large palpable tumors. Leiomyomas can be solitary or develop as a group of tumors. However, they are benign and do not spread to other parts of the body. In extremely rare cases, uterine fibroids may become malignant and turn into a sarcoma (leiomyosarcoma).

Fortunately, the presence of a group of leiomyomas does not increase the risk of malignant transformation.

One of the main risk factors associated with leiomyoma (also known as uterine fibroids) is genetic mutations in smooth muscle cells. Additionally, the female steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone can be linked to fibroid growth due to their effect on cell division and the increase in certain growth factors.

Therefore, the higher the levels of these hormones, the greater the risk of developing leiomyomas. Elevated levels of female steroid hormones are associated with pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause.

Estrogen levels decrease during menopause, which may lead to a tendency for fibroids to contract during this time. Lastly, rare genetic conditions such as hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome) can lead to the development of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas.

Subserosal fibroids are a type of leiomyoma that can arise beneath the perimetrium, which is the serous outer covering of the uterus. Subserosal fibroids can extend beyond the uterus and even attach to other surrounding organs, receiving blood supply from them.

Intramural fibroids arise within the wall of the uterus. They are the most common type of fibroids and can be associated with infertility, spontaneous abortion, fetal malformations, and premature birth.

Submucosal fibroids arise just beneath the endometrium, the thin innermost layer of the uterine wall. Submucosal fibroids can grow into the cavity of the uterus, changing their shape (pedunculated fibroids) and creating a risk of infertility, spontaneous abortion, fetal malformations, and premature birth.

The symptoms associated with uterine fibroids depend on their number, size, and location. Most fibroids are small and asymptomatic. Larger or multiple fibroids can cause abdominal or pelvic pain, lower back pain, dyspareunia, urinary retention, frequency and urgency, infertility, and heavy or prolonged menstruation, which, in turn, can cause iron-deficiency anemia.

Fibroids can cause pain if they exert pressure on nearby organs, such as the cervix or rectum.

The treatment of uterine fibroids should be personalized for each individual case. Considerations such as size, location, symptoms, age, and the desire to maintain fertility should be taken into account when choosing a treatment method.

Asymptomatic fibroids usually do not require treatment. Symptomatic fibroids, on the other hand, can be removed with non-invasive techniques that induce fibroid contraction. For example, uterine artery embolization.